The Tricks before the Treats

If you were born anytime post 1940, you probably spent your Halloween nights dressed up, going from door to door and yelling “trick or treat!” in search of candy. You probably knew growing up that the phrase was supposed to be a sort of ultimatum for your neighbors- they give out treats, or the kids give out tricks- but most kids were in it mainly for the treats. Sure, there was the occasional soaping of a window or some good-natured toilet papering, but real property damage was pretty rare.

Things were a bit different when your grandparents and great-grandparents were kids. Over the last century, Halloween has evolved from a night of mischief and mayhem to a night of costumes and candy.

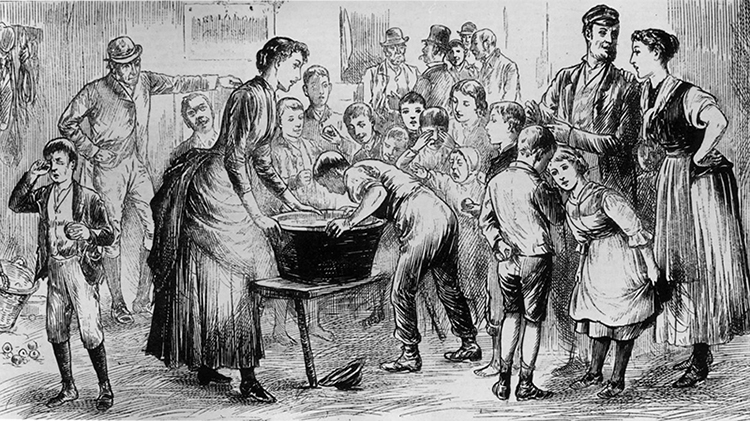

Halloween in America didn’t really take off as a holiday until the mid-1800’s when immigrants from Scotland and Ireland came to these shores fleeing the potato famine. At first, Halloween was celebrated mainly within these ethnic communities and included many traditions that were already age-old, such as telling ghost stories, bobbing for apples, and fortune telling games. It was common for Irish children and young people, both in the old country and here, to dress up and get into mischief on Halloween. Hitting one another with bags of flour and stuffing cabbages down chimneys were typical Halloween pranks in these immigrant communities.

Some say that the tradition of mischief-making on Halloween goes all the way back to the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain. Celebrated at around the same time of year as modern Halloween, Samhain was the Celtic new year and a night when spirits from the Otherworld were supposed to have easy access to our world. Imitating troublemaking spirits on this night was one way of driving them off.

However it got started, by the time Halloween became a nationwide holiday in the late 1800’s, mischief-making was alive and well. In rural areas, it was popular to turn over neighbor’s outhouses and let livestock loose. One great-grandmother recalled a night of particularly satisfying shenanigans that involved putting a neighbor’s wagon on his roof. An editorial published in the Nebraska State Journal in 1883 called Halloween “the worldwide holiday of the vicious small boy”.

Often, in rural areas pranks were targeted at the village grump. A great example of this is the Halloween scene in the movie Meet Me in St. Louis. In the film, which takes place in the early 1900’s, the children dare one little girl to go to the house of an older man who is a bit of an outcast and throw flour in his face when he opens the door. In real life, other adults usually looked the other way at these targeted sorts of pranks ( and probably laughed along in secret).

It was in the cities that the real mayhem went down. Pranks directed at the general public, such as an incident in 1894 where 200 boys threw flour at genteel people driving streetcars in Washington D.C., caused an outcry. In 1887 there were reports of chapel seats coated in Molasses, and in 1888 there were some incidents involving pipe bombs. In some cities, Halloween became an excuse for riot-like activity. There are reports of Halloween troublemakers throwing bricks through windows and slashing tires. By 1920 many communities were desperately trying to provide alternative activities to young people.

During the 1920’s and 30s organizations like the Boy Scouts organized school carnivals and neighborhood trick or treating outings to help keep kids out of trouble on Halloween night. Halloween parties had always been traditional for adults, but now many communities expanded on this idea to create carnivals and parades that everyone could participate in. Trick or treating as we know it today seems to have formed when children and teens broke into smaller groups at carnivals and began going door to door. It was described at the time as a “private parade”.

The trick part of “trick or treating” was slow to go away, and the practice was controversial at first. Some people viewed it as a form of extortion and were concerned that if the children were not satisfied with the treats given, then property damage would be the result. Alarmed adults described some early trick or treaters as “gangs” who intimidated them into handing out candy. During the early days of trick or treating, failure to provide candy usually meant that your windows would get soaped, or your garbage would be spread across your yard. The phrase “trick or treat” was first used in the U.S in a Portland, Oregon Newspaper article published in 1934 that was reporting on Halloween pranks (the phrase was seen much earlier in Canada).

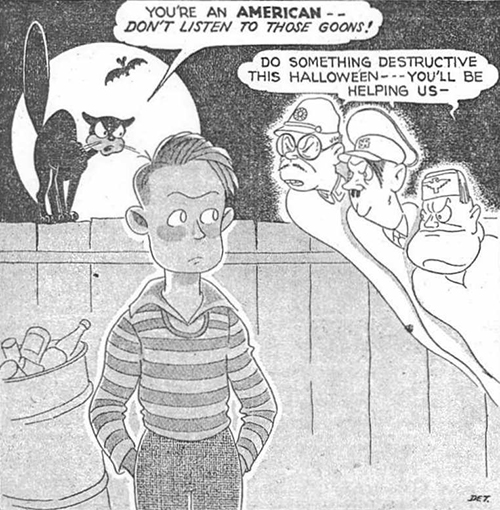

As time went on, the trick part of “Trick or Treating” eventually fell away. This was partly due to the media campaigns during WWII that discouraged young people from harassing strangers, who could be “tired war workers in need of rest”. Cartoons also did their best to influence children toward the more polite, candy oriented version of trick or treating. Throughout the 1940’s and 50’s reports of Halloween vandalism steadily fell.

In some parts of the United States, the Halloween tricks were not abandoned but just bumped to a different night. October 30th is designated as “Mischief Night” in places like the American South and the Midwest. Due to the heavy Irish influence in the South, October 30th is often referred to as cabbage night. Pranks on Cabbage Night usually involve leaving rotten vegetables on porches or smearing them on windows. In the Midwest, it is often called Gate Night because the pranks mainly consist of opening gates and letting livestock roam free. In Detroit, October 30th is referred to as Devils Night and has recently been associated with gang activity and arson. In the 1980’s so much trouble was caused on Devils Night in Detroit that a curfew was put into place for minors on October 30th and still exists to the present day.

Most modern homeowners will not experience any tricks this Halloween, but if you do wake up to toilet paper in your trees remember that those darn kids are just following in their grandparent’s footsteps.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.